THE end of a year of wandering in the eastern Pacific found me in Australia. With

a map spread out on the hotel table before me I was casting longing eyes in the direction

of the Solomon Islands those mysterious little volcanic worlds where black savages,

still cannibals, move like shadows through the jungles.

Every one I met attempted to dissuade me from the journey. I would find no accommodations,

they said; there were devastating fevers; the natives were murderers and cannibals;

I would be shot or eaten or both. Nobody, I was assured, ever went there. But after

many thousands of miles of wandering I had long ago discovered that the places where

"nobody" went were sure to be the most interesting.

The steamship office, scenting a prospective customer, was more encouraging, but

even their people admitted that little was known of the interior of the islands and

that "nobody" went there. But they gave me some useful hints as to equipment,

clothing, quinine and where NOT I to go.

It was a ten-day sail to Guadalcanar, an uneventful voyage that gave little promise

of the excitement in store for me. Guadalcanar proved rather civilized. The missionary

spirit pervaded the place. So one day, not long after my arrival, found me bartering

with a deep sea trader to charter a whaleboat and a crew of four Solomon Islanders.

I knew that I could never return to civilization without having penetrated the mysterious

fastnesses of the mountains and dispelled forever the bugaboo of cannibals. A bargain

was struck. Four missionary-led islanders were found to comprise my crew. In addition

I had the good luck to pick up two Tahitians, stranded sailors from a wrecked vessel,

for skipper and mate. How different those big, children Tahitians were from the swart,

black simian Solomon Islanders.

And so we set sail upon our eventful cruise. Where is the boy who has not dreamed

of cannibals, head-hunters and miasmic swamps, of weird rites and grisly ceremonies?

This expedition of mine was in the nature of a boyhood dream come true. It was certainly

a curious experience to stay in a place where murder and robbery and assault were

permissible diversions for any one so disposed. For in the Solomons, official reports

notwithstanding, each man is a law unto himself, and in the out-of-the-way places

his life rests entirely upon his own ingenuity and the steadiness of his aim. There

is no other place in the world that I know of where an uncivilized savage race is

to be found in a self-ruling condition. Rifles stand loaded in the houses of every

white settler and no man ventures abroad without a Colt slung about his waist.

Perhaps a hundred miles from Guadaleanar is a small volcanic island that rises straight

out of the sea. The natives call it Boukai. For longer than the memory of any living

man there has been a lake in the top of the mountains, lying in the extinct crater.

The natives whispered strange tales of this little body of water: in the olden days,

when rivers of fire ran down to the sea, the savages appeased the wrath of the gods

of the volcano by throwing human sacrifices into the fire pit. But the passing seasons

wrought great change. The fires were subdued. A lake appeared within which strange

forms of life might be found. There were shrimps whose claws were shaped like human

hands, and eels with ears! Looking toward the mysterious heights as we sailed down

upon the island, I would have believed anything of the place, for a lonelier, more

forbidding spot could not be imagined.

But we saw a sight that surprised us. From the top of the crater, where the lake

was supposed to be, a thin column of smoke was rising. The volcano was no longer

extinct. This excited our crew of Solomon Islanders. Not a man among them could remember

when the crater had been active. To them it had some sort of evil portent, perhaps,

and they were in a great state of unrest.

APU and Roti, the two Tahitians, were in a solemn mood. What did I intend to do in

that evil spot, they demanded -- climb to the volcano?

"Of course," I answered. "What else?" My mind's eye had already

taken many feet of rare film of an extinct crater bursting into action.

"Aita! Sperry-tane," said Apu dubiously. "If we go to the crater it

will be necessary to hire a party of guides. These men of ours would not know the

way and they would be terrified. If we left them behind they might seize the boat

and leave us stranded here to be eaten by those devils!"

"We will not leave them behind," I answered. "They shall come too.

But, Apu, I cannot return to my valley in America without taking pictures of that

volcano, of the eels with ears and the shrimp with human hands!"

"Of course," assented Roti. "We are ready, Sperry-tane. I will prepare

the equipment. We will need more ammunition."

But it was not without a few misgivings that we landed two hours later upon a deserted

beach. We had approached the island unknowingly upon the side opposite the settlement,

where the single missionary and trader lived. Nothing but solitude greeted our eyes.

We did not know that the jungle swarmed with black half-human beings whose eyes were

following our every movement. But our crew of Solomon Islanders knew and they were

thoroughly frightened. They huddled together near the boat as if they would take

flight at any moment.

"The trees are filled with men," said Apu slowly, peering into the jungle.

"Try and induce their chief to come out. Give him some tobacco and some beads.

Tell him our only desire is to climb to the top of the mountain and that we will

leave unmolested his people, nor kill any pigs or birds."

After much persuasion Apu prevailed upon one of our now panic-stricken crew to address

the unknown chief hiding in the jungle. Still nothing but silence came from the black

trees. Our man was talking in a faltering voice, the ugly staccato speech of the

islands, transmitting our message.

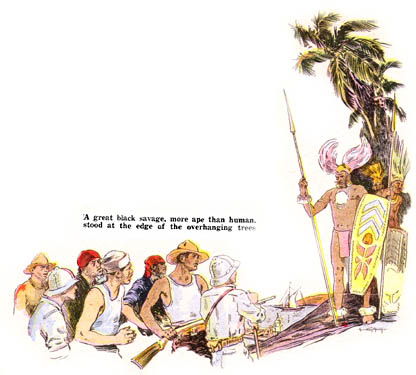

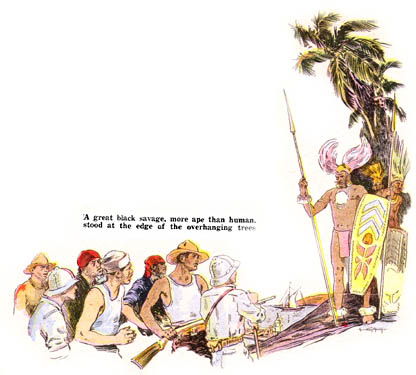

Then for the first time I saw something move. A moment more and a great black savage,

more ape than human, stood at the edge of the overhanging trees. He wore only a geestring

about his middle, and his face and body were streaked with red and white clay, limning

weird and grotesque patterns with awe-inspiring effect. In one hand he held a long,

evil-looking spear. Upon his head was an elaborate arrangement of plumes from the

bird of paradise. The lobes of his ears had been pierced and filled with huge disks

until the stretched skin fell to his shoulders. All in all, he was an impressive

and uninviting sight, and we all fell back a foot and felt for the reassuring touch

of our Colts. Our crew was now plainly terrified and had not Roti stood between the

men and the boat I am sure they would have bolted for the open sea.

But he proved quite amenable to reason, this imposing cannibal. Through my interpreter

I explained that I wanted guides to take me to the top of the Smoking Mountain; that

we were peaceable people who meant them no harm, but that their reputation was unsavory,

to put it mildly; that the guides must perform their office properly and lead the

way, as guides should, and that the very first man who attempted to leave his appointed

place. . . I stopped and patted the Colt significantly. I promised them 100 sticks

of tobacco, a case of salmon and two bolts of red calico. It was wealth for a prince

and turned the tide in our favor. We must indeed be millionaires. The chief would

give us as many men as we wanted. He himself would accompany us. But we must know

that the way was long. As it was now late afternoon it would be necessary for us

to spend the night in his village in the mountains.

Apu and Roti were dubious, but I thought that with a little strategy we might gain

our ends with a minimum of danger. So I accepted the chief's offer, adding that I

could devote only one day to the journey, as the British cruiser Kittewake would

put in at this port on the morrow and I must meet the Captain, who was an old friend

of mine. The chief received this information without batting an eyelash, but I knew

that I had given him something to think about. British cruisers had punished recalcitrant

natives too often and too severely to be taken lightly.

However, the natives of Boukai, though treacherous and cannibalistic, are not in

the habit of killing white people on sight. They will murder you, as they have murdered

many, if they think they can profit by your death or if they have taken a personal

grudge against you and can kill you from ambush. But on the whole they have no particular

objection to you --provided they don't think you are casting spells of sorcery over

them or putting a curse on their island. Being suitably introduced you can beard

the Solomon Islander in his mountain lair and come off none the worse for the encounter.

AND so, without more discussion, we off, leaving two of the most trustworthy of our

crew armed, to guard the boat. They looked particularly unhappy as we stalked away

without them, but I was convinced that no harm would come to them.

The chief's name, I learned, was Kanna. He had about twenty men with him. Accompanying

me were my two trustworthy Tahitians, a faithful and reliable help in any emergency,

and two of my Solomon Island crew, whom I deemed it better to leave unarmed.

We fought and tore our way through the jungle, up slopes so steep that we crawled

on our bellies or slid with clenched hands and feet down into pits of destruction.

The overhanging canopy of densely knitted leaves and vines shut out the air and we

sweltered in the fetid heat. For four hours we toiled upward through the jungle.

Once, through a rift in the trees, I caught a glimpse of the smoking crest of the

volcano.

Soon we came upon a narrow pig path. It was the "road" leading to the chief's

village. Surely they had found it only by instinct in that impenetrable jungle. As

the village came in sight a score of naked natives rushed to meet us. Kanna hurled

commands at his people and they separated in a dozen directions.

The sun was setting behind the volcano, and dusk made of the little cannibal village

an eerie spot. The grass houses were high and the roofs peaked. Many rains had bleached

their color to a ghostly white and they loomed through the gloom like unreal figures

in a dream.

Kanna assigned a house to me and the two Tahitians and another to the two sailors,

but the men refused to leave our side. They were plainly frightened. And did not

blame them. There was a sinister undercurrent to the very air of the place that was

dispelled only by the reassuring presence of a steel-blue Colt and plenty of cartridges.

All night long, as we feigned sleep, we could hear the low drone of excited, hushed

voices, and from somewhere came the chilling sound of a drum beaten in intermittent

tattoo, like a signal: it was, answered by another tattoo, faint and far off, that

I thought might be an echo but that the quick ears of Apu and Roti recognized as

having a different rhythm.

But the night passed uneventfully and day found us laboring up the slopes of he mountain.

Five hundred feet from the rim of the crater all vegetation was burned and dead and

we walked buried almost to the knees in cinders. The heavy canvas of my puttees was

cut to ribbons by the knifelike edges of the lava, but the leathery-skin of the savages

seemed to go unscathed. We must have presented a curious procession as we toiled

up that heartbreaking slope. Kanna led the way, dressed in all his paint and paradise

plumes. Ten men followed behind him, poles on their shoulders from which were slung

a dozen squealing pigs that were to be offered as sacrifices to the god of the volcano.

It didn't require very much imagination look back a few years and see a similar procession

climbing the long slopes with human beings slung in place of the pigs.

As we approached the top of the crater the air was filled with sulphurous fumes which,

added to the great altitude, made breathing difficult and painful. A heavy wind fortunately

blew the stroke in the direction opposite our ascent. The earth grew warmer beneath

our feet.

At last we gained the rim and climbed cautiously to the edge. What a sight greeted

our eyes! Nothing else in the world is so impressive as an active volcano, can strike

such unprecedented terror to the human heart, or can make man seem so unutterably

in insignificant in the scheme of living things.

NOT a hundred feet below us lay a lake of living fire, a pit of hell, where waves

of glowing lava writhed and twisted and dashed upon the rocky walls, just as the

waves of the sea were beating the cliffs of Boukai. It drew you with a strange fascination,

glowing with every devilish color of the spectrum, terrifying and alluring. You wanted

to run, and you wanted to jump in.

Kanna and his men were intoning a strange chant as they prepared to throw the pigs

into the fiery furnace. Their weird cries rose above the hiss of smoke and steam

and mingled with the terrified squeals of the doomed animals. It was an impressive

scene, these wild-looking black savages huddled on the brink of that pit of death,

chanting their bloodchilling invocations. It occurred to me that it would make a

rare movie. With Apu and Roti, who carried camera and tripod, I stole away to a place

on the rim, perhaps a hundred yards away, where I could get a good view of' cannibals,

pigs and crater.

The savages were lashing themselves to a fury. Their voices rose to shrieks. They

cut themselves with knives and bits of shell. Blood was streaming over their sweating

bodies. The pigs, as if with some premonition of impending doom, wailed and tried

to escape.

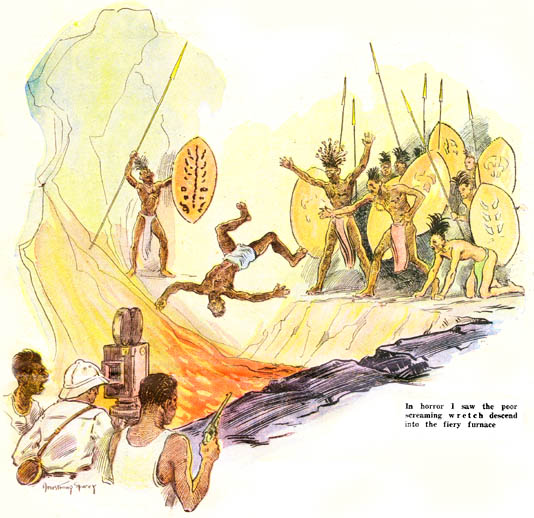

And then pandemonium broke loose. In one swift second some instinct stronger than

threat of battleship or fear of rifles took possession of the cannibals. With horror

I saw that they had seized upon one of my Solomon Island men. The poor devil was

screaming aloud with terror. The other man had taken to his heels, dashing to us

for protection like a stricken animal. Kanna and his men had rushed to the edge of

the fiery pit the human victim held by a dozen savage hands. At the same moment Apu

raised his Colt and fired.

With one convulsive heave the cannibals shot the struggling victim out into the air.

In horror I saw the poor screaming wretch descend into the fiery furnace and the

livid, hissing lava closed over him.

But Apu cried out with alarm, and looking up I saw that the now maddened savages

were dashing toward us. Their intention was unmistakable. We were no match for the

bloodthirsty horde, and, hurling an order at Apu to drop the camera, with one accord

we started for the protecting jungle, sliding, falling, pitching down the steep descent

of cinders. Once in the trees we would be comparatively safe from the spears of our

pursuers and they could hardly aim with accuracy in their breakneck plunge after

us.

The terrified sailor who had run to us for protection led the way. If we could keep

up with him I knew that some instinct would find him a way through the jungles to

the sea.

The day that followed will always seem like a nightmare. We fought and tore our way

through the forest, the knives of Apu and Roti slashing right and left. Our pursuers

seemed always just behind us. Once, and once only, Apu stopped and turned. His Colt

barked out through the stillness and a scream of pain answered.

"0 Kanna!" he announced grimly, and I knew that once their chief was gone

we were comparatively safe. The cannibals seemed to lose heart, for soon we no longer

heard them crashing behind us.

That night, in clear moonlight, we staggered more dead than alive out upon the beach.

And there pandemonium seemed to have broken loose. The beach was black with gesticulating

savages and the name of Kanna came to my ears. The two boys whom we had left in the

boat had apparently shot off all their ammunition and were dancing with fright, screaming

something unintelligible to their tormentors.

As we ran to the boat and made for the water Roti and I fired half a dozen shots

in the air. The cannibals scattered in alarm. But the two boat boys had run. They

were incapable of distinguishing friend from enemy. As we attempted to climb over

the gunwale they were at us with their knives. One of them slashed Apu's arm from

elbow to wrist and I felt a sting of pain stab deep into my shoulder. Then with a

club Roti knocked them both insensible and we seized upon the oars and regained our

ship.

That night as the gentle wind from the mountain filled our sails and we slipped quietly

out through the pass in the reef and the wound in my shoulder had been dressed and

Apu lay with his bandaged arm on the deck, I looked up at the volcano which glowed

with a fitful, evil glare against the dark sky.

My first adventure with cannibals had been disastrous enough. The savages of the

Solomons may be tamed and trained in time: the influence of missionary and teacher

may break their savage, spirits and let light into their darkened brains but that

day is not yet. Murder and hate and treachery still stalk the jungles and breed in

those miasmic swamps.

© The Estate of Armstrong Sperry